Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust

by Victor Fiorillo and Liz Spikol, Philadelphia Weekly - January 18,2001

Philadelphia dumped 4,000 tons of toxic ash onto a beach in Haiti in 1988. Thirteen years later, the ash and its destructive effects still plague the people of the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere.

So what are we going to do about it?

"After this work, I wake up in the middle of the night. My nerves feel bad. And the rash, it is bad. I really scratch and scratch and scratch. And also spinning, dizzy. There is something with my nervous system. Something attacks my nervous system. I feel depression I never felt before this."

Fifty-two-year-old Raphaël Elifaite is a resident of Gonaïves, Haiti, the former resort town where toxic waste from a Philadelphia incinerator was dumped in 1988. When the ash was finally removed on April 5, 2000, Elifaite was one of those who worked to clean it up. Before, he says, "I was always fine."

Now Elifaite wants medical treatment, as do many of his colleagues. "I want to go to a hospital in Philadelphia and have them check me out all the way."

There are many men like Elifaite in Haiti. Men who speak an angry French Creole at videotaped press conferences while wearing T-shirts that say "Retour á Philadelphie," or "Return [the ash] to Philadelphia."

A map on the shirt shows Haiti and the East Coast of the United States. A red arrow goes from Gonaïves to Philadelphia. On the bottom are the words "Déchets toxiques Gonaïves," or "Gonaïves' toxic waste."

That this phrase now implies Gonaïves' ownership of the ash is revealing. It has become their problem, but it didn't start out that way. It started as our problem. It started out in Philadelphia.

Roxborough, to be specific.

The History

You might not remember the Philadelphia trash crisis of 1986. For most civilians, it only lasted

20 days, after municipal workers walked off the job, leaving the trash behind.

Like all Philadelphia strikes, resolution came just before complete disaster, and most people in the region probably forgot all about it. But there was another trash-related problem to deal with, one that focused on Philadelphia's incinerator ash. We had too much of it--and no way of getting rid of it.

Finally, Joseph Paolino & Sons signed a $6 million contract with the City of Philadelphia to make the ash go away. Paolino & Sons subcontracted Amalgamated Shipping Corp., the operator of a barge called the Khian Sea, to dump the ash in the Bahamas, where Amalgamated Shipping was headquartered.

On Sept. 5, 1986, the Khian Sea left the Delaware River carrying roughly 14,000 tons of ash. "I had opposed it ever since it was shipped out," says City Councilman David Cohen. "That was the time when [then-] Mayor Wilson Goode was acting desperately. Philadelphia had a responsibility. It was Philadelphia waste. I thought it was Philadelphia's responsibility not to dump it in any waters. It wasn't even dumped on a landfill."

It wasn't dumped anywhere, initially, because the Khian Sea kept getting turned away. It was first turned back by the Bahamas, whose government was deterred by the barge's dangerous content.

Joseph Paolino & Sons filed suit against Amalgamated Shipping for breach of contract, but the boat circled the Caribbean Sea for the next 16 to 18 months, trying unsuccessfully to dump the ash in Bermuda, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Guinea-Bissau and the Netherland Antilles.

The resistance to the Khian Sea was due largely to the efforts of Greenpeace. "At that time," recalls Ann Leonard, who now works with Essential Action, "Greenpeace really monitored the movements of the barge. It kept changing ports, paint and names, so we kept sending telex messages to various ports to warn them."

To warn them of what?

"The danger."

On New Year's Eve, 1987, the Khian Sea arrived in Gonaïves, Haiti, a small, impoverished port town on the country's west coast. Contracts signed by the Haitian government, which were supposed to reveal the ship's contents, described the ash as "fertilizer." Jerry Schwartz, a writer for the Associated Press, reported that the government officials who signed the contract were two brothers of Col. Jean-Claude Paul, "a corrupt leader of the Presidential Guard."

And though the Haitian government would turn around the next day and ask to have the ash removed, 4,000 tons of the ash were dumped on the beachfront at Gonaïves. On Feb. 2, 1988, the Haitian Minister of Commerce, Mario Celestin, demanded the Khian Sea take the ash back and find a different dump site. He even went so far as to issue a Court of Justice injunction for the ship to recover its waste. But the boat left in the middle of the night without reclaiming the waste. It still had roughly 10,000 tons of Philadelphia ash to dump.

"Four of us from Greenpeace went down a few days after the ash was dumped," says the activist group's Kenny Bruno. "We documented that it was dumped and took samples."

Leonard and Bruno followed that up with what would become years of work trying to get the ash removed from the small beach. Immediately after the dump, Leonard says, "We worked with Haitian groups to try to get it cleaned up, but it was very difficult with the absence of democracy in Haiti." Leonard and her Greenpeace cohorts would have to wait until Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected and democracy was established.

Meanwhile, the Khian Sea had its own struggles of sovereignty. After the initial dump onto the beach at Gonaïves, the barge attempted to bring the remainder of the toxic ash back to Philadelphia. Amalgamated Shipping refused to take responsibility for dumping the ash in Haiti and its boat was refused permission to dock at Pier 2, which was owned by Paolino & Sons.

The Khian Sea dropped anchor in the Delaware, waiting for permission to unload the ash. That night, fire destroyed Pier 2.

The Khian Sea then fled the United States, against Coast Guard orders, renamed itself "Felicia"

then "Pelicano" and ultimately arrived in Singapore in November 1988--without the ash. The captain of the boat later admitted in court that the balance of the ash had been dumped at sea.

Philadelphia's ash--its problem toxic waste--was gone, adrift somewhere in the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

Except, that is, for the 4,000 tons in Haiti. That pile of ash remained at Gonaïves, "sitting," as the AP's Jerry Schwartz reported, "uncovered on a beach where children played."

But activists still had hope that there would be a resolution favorable to the Haitians. On Feb. 17, 1988, Kenny Bruno, along with a team of Greenpeace investigators, arrived in Gonaïves and met with the mayor and the Haitian prime minister, who immediately announced a ban on all waste imports into Haiti. It was too late for the beach at Gonaïves, but it would prevent further dumping.

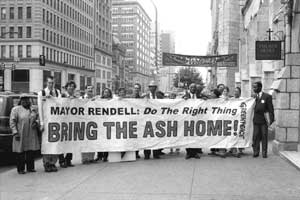

A few days later, Greenpeace delivered bottles of ash from Gonaïves to the deputy mayor of Philadelphia, Robert A. Brady, and led a protest at Pier 2. Between 1988 and 1996, Greenpeace and other environmental activists made numerous attempts to have the ash removed from Gonaïves, but were consistently stonewalled by corporations and governments that did not want to accept responsibility.

Ann Leonard was part of the negotiations early on. "[Haitian Communications Project president] Ehrl Lafontant and I met with Mayor Goode's staff," she recalls. "Mayor Goode said that he agreed it was a problem, and that they would help bring the waste back. Goode said that if we could get the ash back to Philadelphia, the city would [accept] the [transfer of the contract's title]. Goode told us that the city was so broke, they were using volunteer lifeguards at the city pools."

This was the last time any Philadelphia official would take responsibility for the ash. Mayor Goode's offer to assume the contract again--which officials would later deny--was as proactive as Philadelphia was willing to get.

Dr. Franz Latour, president of the board of the Haitian Community Center of Philadelphia, has been in the city since 1969. In strongly accented English, he says, "They were not willing to do whatever was necessary to fix the problem. Essentially, they had been hanging on to this idea that they and a contract with a company who subcontracted to another company, so [legally] they no longer had an obligation because it was no longer in their hands. ... I see it from the perspective of a big city in a big country--a rich country--doing something unfair and unjust to a poor, small country."

Mayor Goode may have felt the same way about the ash, but was unwilling to pay for its removal. Given Haiti's status as the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere, the chances of grassroots or even government monies being raised to complete the removal were slim.

So the ash stayed. The enormous black sooty pile covered the beach, the particles blown by the wind. In early 1990, according to the Haitian Collective for Environmental Protection and Alternative Development (COHPEDA), the Haitian government created a bunker for the waste, a stone basin of sorts that would hold the ash. Though it would be housed in an uncovered structure, at least it would contain the toxins--or so they thought.

How Toxic?

Gonaïves locals were employed to move the ash to its new site, on a hilltop two and a half miles north on Mont La Pierre. But according to COHPEDA's dossier, Haitian "journalist Herby Dalencourt reports that his cousin, Smith Joseph--[who was] working in the Ministry of Public Work's project to move the wastes--did not survive the operation. 'My cousin had skin lesions and visual problems,' says Dalencourt. 'The workers hired at that time wore neither gloves, masks, nor boots.'

"A tractor driver who, like others at the time, did not protect himself, died in a similar manner. ...

People living close to the dump site complain of the loss of many heads of cattle following the consumption of grass growing on the hill near the basin. Haitian environmental specialists indicate that because of the lack of reliability of the basin, there is a possibility for toxic substance infiltration and contamination of the aquifer."

And what about the toxic content of the ash? Much of the activism was based on the assumption that Philadelphia's trash from its Roxborough incinerator was "dirty"--filled with toxic chemicals. As reported in the Daily News and Inquirer at the time of the dump, environmentalists alleged the ash was "tainted with lead and mercury." Yet the city and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources found the ash to be "non-hazardous,"

which is consistent with ash from any municipal incinerator. But if this is true, why do health problems continue to plague the citizens of Gonaïves?

When the EPA issued a flash report on "Philadelphia Incinerator Ash Exports" that were destined for Panama--the same ash that found its way to Gonaïves--it found that "samples of the ash have been shown to contain levels of lead, cadmium and benzene which occasionally exceed hazardous waste thresholds, as well as a wide array of heavy metals and toxic chemicals.

Significant amounts of these substances in the ash will very likely reach wetlands and aquatic environments, possibly damaging or killing aquatic life and entering the human food chain."

These results were also published in a January 1995 report by the Greenpeace Exeter Research Laboratory at England's University of Exeter, which offered an independent analysis of the Haitian ash. The conclusion? "The findings from this brief investigation do not concur with the city, EPA and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources, which found this ash to be 'non-hazardous.'" Among the chemicals found cadmium and arsenic, among others.

Later, the U.S. would insist the ash be treated with the chemical Vapam HL. Amvac, the chemical corporation that manufactures Vapam, warns of potential health effects, including eye problems, nausea, dizziness, weakness and on its "Material Safety Data Sheet," it says, "Danger! Harmful if swallowed. Harmful if inhaled. Harmful if absorbed through skin. ... Do not get on skin or clothing. Avoid breathing vapor or spray mist. Do not get in eyes." And, most damaging of all "Toxic to fish. Do not contaminate water bodies."

Haiti's Minister of Environment Daniel Brisard is now engaged in an environmental-impact assessment along with an assessment of the workers' health. Though he was quiet about the environmental damage caused by the ash's longtime presence, he did say, "We would welcome any support from Philadelphia and the U.S., but we are not going to wait."

The History, Part II

Haiti's COHPEDA remains the most forceful group in the battle to remove the ash and continues to galvanize the discussion of reparations today. COHPEDA's dossier on the case, titled "Toxic Waste Dumped at Gonaïves a Problem to Solve!," notes that as early as 1992, when Greenpeace and Haitian representatives met with then-Mayor Ed Rendell, "an agreement to repatriate the ash seem[ed] to be taking shape."

In other words, the city of Philadelphia was still entertaining the notion of removing the ash and bringing it back for proper disposal. But Mayor Rendell would not be so easy to convince. (At his office's request, we faxed over a synopsis of the story with a request for comment. As of press time, Rendell had not responded.)

"Rendell was not helpful," Kenny Bruno recalls. "It was stated officially by his chief of staff in a meeting to me that [the city] would give $50,000 [toward the ash's removal from Gonaïves].

This was confirmed by the newspapers. ... There were a couple of landfills that were possible."

Things changed some in August 1996, when Louis Paolino of Eastern Environmental Services--who was executive vice president of Joseph Paolino & Sons at the time of the Gonaïves incident--applied to the New York City Trade Waste Commission (NYCTWC) for a license to transport trash in New York City.

The commission soon discovered the link between Louis Paolino and the Haitian ash dumping.

They conditioned his licensure on Eastern Environmental Service's financial contribution to the removal of the ash from Haiti. The commission's Russell Bixler says now, "We found Paolino to be significantly involved in the company that got rid of the ash. Since [one of] our statutory responsibilities is to pass on the integrity of our applicants, we thought we should do something about this situation. ... At the end of the day, EES agreed to put up some percentage of the money. At that point, the obligation changed as a result of mergers and acquisitions."

(When Philadelphia Weekly called Paolino for comment, we could only speak with his assistant Pat Torriero, who said, "He said to tell you that his comment is 'no comment.' And that's a direct quote.")

Aside from asking for money from Paolino, the NYCTWC asked Philadelphia for a financial contribution as well. On Sept. 11, 1997, the chairman of the Waste Trade Commission sent a letter to then-Mayor Ed Rendell, requesting that Philadelphia commit $50,000 to the cause.

Wrote Chairman and Executive Director Edward T. Ferguson III " ... We hope you agree that it would be appropriate for the City of Philadelphia to commit the relatively modest sum of $50,000 toward the removal of its incinerator ash from an illegal dump site in an impoverished foreign country.

"The Commission's staff has devoted many hours to coordinating this effort, and we will continue to do so. But the City of Philadelphia's help is needed to ensure that adequate funds will be on hand to clean up this decade-old environmental mess."

Gregory Rost, the mayor's chief of staff at the time, responded by attempting to absolve Philadelphia. Rost stated that the "... city never granted any authorization for the disposal of the city's incinerator residue in the Bahamas or anywhere outside of the United States."

At the same time, Rost wrote, "The City applauds the Commission's desire to support and endorse what, at least on its face, appears to be an environmentally worthy cause." Rost went on to say that many of the points in Ferguson's letter were "misleading" while others were "simply factually untrue." He ended by saying, "Again, the City commends your efforts at what appears to be an admirable effort to support an environmentally friendly project. The City wishes you the best in this effort."

The city also stated that if it was to help in any way, the effort must remain "cost neutral."

Ann Leonard says she was "absolutely shocked" by Philadelphia's refusal to contribute the $50,000. Russell Bixler is not as bothered "In a way, it's not quite fair to say Philadelphia dissed us. ... My understanding is that Philadelphia is holding on to the money until it was needed." But Ann Leonard is less convinced. "From the initial contact, Rendell flat-out said, 'Absolutely not.'"

In January 1998, the 10-year anniversary of the dumping, various Haitian and American groups formed Project Return to Sender (RTS), which was committed to having all of the ash returned to Philadelphia before May 31, 1998, the expiration of Paolino's agreement to contribute to the Haitian ash removal with the Waste Trade Commission.

Leonard says, "Over the course of a couple of years, RTS sent letters, went to City Council and testified there, brought the ash to show them ... A group of Philadelphians went to Haiti and protested at the U.S. Embassy. RTS sent information packets to every City Council member.

When City Councilman Cohen tried to introduce a resolution, it was clear that the other members had not read their packets. They said, 'We already paid once to have it removed, so why should we pay to have it moved again?' We kept running up against a solid wall."

The Haitian Community Center's Dr. Latour remembers those Council meetings well. "The idea," he says, "was to have the city take responsibility for the trash. I told City Council that it was trash that came from Philadelphia but it wasn't Haiti's fault that the ash eventually was mishandled and that Haiti is a poor country and they just could not afford to have that danger sitting at their shore. It was a matter of justice ... a matter of humanity that the city should take care of its own mess."

Local activist Robin Hoy, who had been to Gonaïves on a Witness for Peace mission, remembers the flurry of activism that surged in 1998. "We participated in postcard campaigns and petitions to Mayor Rendell. ... We also requested, but were not granted, a meeting with Mayor Rendell to ask for him to lead an effort to bring the waste back to Philadelphia. The Mayor of Gonaïves wanted to come to Philadelphia and meet with Rendell, and there was discussion of Philadel-phia becoming a 'sister city' to Gonaïves to make amends and show good faith ...

"We also approached the president of City Council, John Street. ... He was at first very supportive, but as media coverage became greater and Rendell refused to respond at all, Street changed his stance to agree with Rendell, that it was not Philadelphia's responsibility." A letter to Street from Ann Leonard from her Washington office at Essential Action informed him that she'd be visiting Philadelphia in the next week. She requested a meeting, but Street never responded.

(As of press time, Street's press secretary, Luz Cardenas, told PW she was still waiting for the mayor's comment on this story.)

On April 7, 1998, five U.S. representatives--Carrie P. Meek (Fla.), Major Owens (N.Y.), Joe Kennedy (Mass.), Esteban Torres (Calif.) and Maxine Waters (Calif.)--sent a letter to Secretary of State Madeline Albright. The letter read "We understand the residents of Gonaïves, the seaside town where the ash was dumped, are deeply worried about the long-term impact of this cadmium- and lead-laced mound which remains in their midst ...

"The fishermen of Gonaïves cannot sell their catch, since Gonaïves residents will not buy fish caught in waters into which the ash has been seeping and blowing. Investors in the area are concerned about the negative impact of the ash on their businesses.

"We understand that a local [U.S.] company ... has threatened to move its ... business if the ash is not returned to the United States. This would deny 800 Haitians employment ... We understand that it will cost a total of $600,000 to remove this ash and properly dispose of it.

However, the company which originally shipped the ash to Haiti has agreed to return it to the United States, provide $100,000 toward its removal and contribute $250,000 in landfill to assure it proper storage in Pennsylvania. ... We ask that you consider providing $250,000 toward the $600,000 needed to remove the ash and properly dispose of it.

"The Clinton administration clearly was not involved in any way in the shipment of this ash to Haiti. However, your commitment to help remove the ash from Haiti would reflect the decency of the Clinton administration ..."

A week later, U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah sent a letter to Rendell saying, "It would be an act of considerable generosity and good will towards the government and people of Haiti if the Philadelphia City Council would make a small contribution of $100,000 ..."

But Rendell said nothing--until, that is, he was publicly confronted by Ann Leonard. "We went to a lavish party hosted by Philadelphia in Washington," recalls Leonard. "Philadelphia was trying to convince the Democratic National Committee to have their convention in Philadelphia.

So we went to this party and walked the receiving line. When I came to Rendell, I put a pin on him that read 'Mayor Rendell Do the right thing--bring the ash home.' There were cameras and other press there. We asked him to do the right thing and to clear Philadelphia's name. Finally, he said '$50,000 and not a penny more.'"

There is no evidence that Philadelphia has contributed a penny.

Finally, last spring, the ash was removed through the cooperation of several entities, including the Office of the President of Haiti, the Haitian Ministry of Environment, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the New York City Trade Waste Commission, which managed the United States' financial contribution. A U.S. company called Arpin oversaw the loading of the ash onto a ship, which departed Gonaïves, at long last, on April 5, 2000. Since then, the waste--our waste--has been floating on a barge off the coast of Florida.

The fate of the ash remains in question. According to Ira Kurzban, the attorney representing the government of Haiti, the ash was originally to be disposed of in South Florida. But now there is a dispute between Waste Management Inc.--which now owns Eastern Environmental--and the New Jersey-based Arpin. Waste Management spokeswoman Sarah Peterson says, "We do not own the ash. We are not responsible for it."

"As far as I know, it is still on the barge off Florida," says Russell Bixler of the New York City Trade Waste Commission. "I'm glad we got the ash out of Gonaïves. I am sorry it has not found a home yet. ... Waste Management controls several landfills where it can go."

"While it was victory in a way, I am a little ambivalent about it," says Ann Leonard. "There's not a real resolution until Philadelphia takes responsibility for the waste."

How much ash is left is still open to question. Ann Leonard wonders "A lot of the ash definitely blew into the sea. I went to Gonaïves three times and the pile kept getting smaller and smaller."

In Haiti, though, the pile of problems continues to grow.

In Haiti

It is Thursday, Nov. 30, 2000. The 4x4, driven by Haitian environmental activist and COHPEDA leader Aldrin Calixte leaves Port-au-Prince for Gonaïves in the early morning.

Port-au-Prince, the capital city, is still tense from the election four days earlier which, while quieter than previous elections, still had its share of pipe bombs and masked gunmen.

Calixte is reluctant to make the trip because of security concerns. He asks his cousin, a police officer, to come along.

There is only one road to Gonaïves, and the first half of it is decent and goes along the coast. It's speckled with small beachfront hotels that house the rare wealthy Haitian and even rarer tourist.

The car passes by a fairly upscale resort. Calixte explains that this was the private beach of former dictator Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier.

As the car gets closer to the port town of Gonaïves, the road deteriorates, justifying the $100 laid out for the shabby 4x4 in a country where you can buy bottled beer for 30 cents. While the coastline is still apparent, there is neither a resort nor any other visible industry in sight.

"Gonaïves, this is Gonaïves," Calixte says and points to a sign that reads, "Toxic Dumps in Haiti Never Again."

While stopped at a gas station just inside town, it becomes obvious that the citizens of Gonaïves are not used to seeing outsiders.

Not only is the town difficult to visit, due both to its isolation and lack of tourist necessities, but the Lonely Planet guidebook on Haiti--one of few such books available--says of Gonaïves, "Avoid the beaches as toxic ash from the city of Philadelphia, Pa., was reportedly buried beneath them in 1988."

A short drive past the most densely populated area of Gonaïves, the 4x4 starts down an access road to the beach, passing run-down shacks surrounded by grazing goats and naked children playing in the dust. It stops at a port access gate, where Calixte rambles in Creole with the guards, who appear leery about letting anyone through. Calixte's cousin Adele flashes his police credentials, and the guards smile and open the gate.

The port is tiny and there is no activity. A soft breeze blows dust all around. Calixte, a small, thin man with a narrow mustache, is anxious to explain what happened here over the past 12 years.

He does his best with his limited English.

The beach looks deserted, and it's hard to believe 4,000 tons of Philadelphia ash once littered this white sandy inlet framed by turquoise-blue waters. Calixte points to the wharf, then to the beach and then to a nearby mountain, Mont La Pierre. He describes how Haitian workers transported the ash over the years.

"When Manigat became president in 1988, he take the ash from here and put in on Mont La Pierre," he explains. "They construct a basin, a bunker. They put the ash in the bunker." Calixte explains the bunker's biggest weakness was its open ceiling because the frequent rain would fall directly onto the ash.

A man in his 20s approaches, and Calixte introduces him as Michelette, a Gonaïves resident and port security guard who worked with the ash in the past few years.

The young-looking Michelette wears a striped cotton shirt. His legs have patches of what look like some sort of white residue. He explains that he was paid 36 gourdes ($2.21) an hour to handle Philadelphia's toxic waste.

Asked if he was given protective clothing, Michelette responds, "I wear a mask and gown ...

The suit was made out of paper." He complains of frequent rashes, something he says he never had before working with the ash.

"I want medicine. I want American doctors," he says and suggests that a delegation of workers come to Port-au-Prince to explain their position. When he participated in a COHPEDA-sponsored press conference in 1999, Michelette started out answering questions calmly, in a mix of Haitian Creole and French. But as the conference went on, he began to get angry, his voice raised.

"We weren't properly protected," he says sharply in the video. His eyes flash and his brows furrow.

Now, Michelette is called away by someone at the gate. Through the holes in the wall of a nearby shed, Calixte points to several black containers labeled "VAPAM HL."

"The ash be treated before ash come to United States," he says.

This "treatment," which was supposed to purge the ash of its toxic properties, was carried out by Haitian workers. And yet, they were told, if the ash was not treated in this fashion, the U.S. would not accept it and it would remain on the beach.

Caribbean Dredging Excavation (CDE) was contracted to supervise the treatment and excavation of the ash. Chris McFadden of the Department of Environmental Protection in Florida says, "The ash is currently benign."

On the beach at Gonaïves today, there are several waste containers from CDE, their contents unknown. There are also several tubs of VAPAM HL remaining.

As Calixte continues to explain the ash clean-up effort, two SUVs speed through the gate and onto the beachfront, screeching to a halt just feet from the shed where the leftover VAPAM HL is kept. A large armed man jumps out of one truck, grabs the table on which a reporter was taking notes and tears them up. He is agitated, screaming.

A man identifying himself as Fritz Thisfeld steps from the other truck, explaining he is the manager of the port and that unauthorized entry is forbidden. (Later that evening, a couple of expatriates and journalists suggest the port in Gonaïves is a major transit point for cocaine passing from Colombia to the United States, which could explain the confrontation at the port.)

Back in the 4x4, Calixte drives from the port up to nearby Mont La Pierre, where the Haitian workers relocated the ash in 1988. Walking among broken chunks of concrete that were once the walls of the bunker, Calixte explains that aside from having no roof, there were holes and cracks in the concrete walls. This allowed the rainwater that would fall on top of the ash to seep out the sides and into the groundwater.

Ann Leonard of Essential Action says that when she visited the bunker and its ash contents in 1998, one of her colleagues pulled an easily identifiable page from the Philadelphia Inquirer from the pile of ash. Leonard says, "I also noticed bits of burnt metal and broken glass," which would indicate the incinerator ash was not as "purified" as it should have been.

Suddenly, Calixte says that due to road conditions, the problems at the port with Fritz Thisfeld and security concerns in Port-au-Prince, it is necessary to leave Gonaïves immediately. He is certain that a delegation of workers will come to the capital on Saturday, as they are anxious to tell their story.

Saturday, Dec. 2 arrives, and there is some doubt that the workers can come to Port-au-Prince.

The trip is expensive and Haiti's infrastructure is unpredictable. But at breakfast at the Hotel Oloffson--a large gingerbread mansion frequented by celebrities when Haiti was a popular tourist destination--a Haitian man named Ronald arrives and sits at the table. He asks that his last name not be used, then says he heard about Thursday's trip to Gonaïves to investigate the after-effects of the ash.

While sipping a cup of Haiti's incredibly sweet, strong coffee, Ronald explains that he is both the pastor of a church in a town close to Gonaïves and an environmental activist. He has been following the story of the ash for some time, and while he is glad that most of the waste appears to have been removed, he does not want the story of Gonaïves to fade from Philadelphia's memory.

"There is people in Philadelphia who care about us. Who think about us. Who do not leave us alone. If those people could find somehow to bring some job to Gonaïves, that would ... be the best thing for us ... Those jobs will last for long and we will survive with them."

Ronald believes that those who worked with the ash and the other residents of Gonaïves should receive medical attention from the United States, to see if there are long-term health effects associated with exposure to the ash.

Forty minutes later, at the COHPEDA offices, Haitian workers sit at a row of school desks, ready to tell their story through translator Jean Fabius, a Haitian telejournalist who says he was instrumental in working with Minister of Environment Daniel Brisard to have the ash removed.

The workers look angry and seem cynical about the possibility of anything being done for them.

Jean Fabius says he and some of the workers met with Brisard and asked that they receive long-term medical assistance, but that the meeting produced no results.

"We would like to have them examined every six months," Brisard says later. But when asked if he feels his government has the money and manpower to do this, he is evasive "That is what I am working on right now." Ultimately, what he's doing for the Haitian workers is unclear.

"I am a scientist," he says testily, "and until proper studies are done, I would not be able to comment. ... Listen, I cannot talk to you about this any more over the telephone ..."

At COHPEDA, the first worker to speak is Kend Noël, who is the first Haitian known to have contact with the ash.

"I was in charge of the pier when the first boat came and unloaded it. I was the one who helped to unload it. They brought the waste here as fertilizer. When we got it off the boat and the boat left ... After a few weeks, the people started to complain ..." When the government responded to the residents' growing concern by building the bunker on Mont La Pierre and relocating the ash, Noël says, "a lot of it remained there still by the pier."

Asked what--if any--effects they believe the ash has had on them, Noël is again first to speak.

"We all have similarities. We all have a rash. We do not feel comfortable. We are not normal.

We feel that something happened."

He adds that he's had problems with his eyes ever since working with the ash and complains of a general sense of malaise. "My head is not good. It was windy at the wharf. I was breathing this thing. It affected me."

Johnson Bien-Aimé corroborates the story. He has the same symptoms, he says, adding, "I never had these problems before."

All of the workers agree that they were in good health before moving the ash. The fourth worker at the meeting, Hybermann Déclé, stands and pulls his trousers down around his buttocks, revealing a serious rash that he allows to be photographed for documentation. The other workers agree that this rash is the same that has plagued them and other workers since they handled the ash initially. Kend Noël says, "We all have rashes on our genitals."

The workers' rashes are clearly visible in the videotaped press conference. One man pushes his nylon shorts aside and pulls his penis out for the camera. It is encrusted with what looks like a white residue. It looks almost deformed.

All of the men agree that the most important matter, at this point, is their health. They want to be brought to Philadelphia for medical evaluations, saying the medical facilities available in Haiti are poor.

Raphaël Elifaite seems to reflect the attitude of the other workers "I have seven children. I feel that I could leave them behind. I don't know. I have always been in good health before this."

"I have documented many of the workers, and they are just getting worse," says Calixte.

The workers, with Calixte's help, draft and sign a letter addressed to Mayor John Street [see page 16], and ask that the letter be hand-delivered to him. They want to meet with the mayor, and say that if the funds can be raised, they'd like to come to Philadelphia next month.

After the letter has been signed, Calixte, who has been the main Haitian environmental advocate involved in the removal of the ash, reads a prepared statement regarding the effects of the ash on the public health, economy and environment. "From the health point of view, we saw that there was an introduction of new type of disease of skin problems ... Also there were people who were stomach sick. Like food poisoning. I talked to the minister of health to see about an evaluation of their health to see if this was related to the ash. This evaluation was never done.

The government did not want to talk about it.

"As for the economy. In the area, there are some salt fields. Salt mines. With the presence of the waste in the area, these activities dropped considerably ... From a fishing aspect, it has dropped considerably. The people in the area do not eat the products from the sea. Financially, [quality of life] has gone down. The people have some needs they cannot provide for. And also not being able to eat the seafood, this has created an impact for their main source of protein.

"It has also created an inevitable impact on the physical environment. The air that they are breathing has been polluted. These are tiny particles. The accumulation is happening. That's why leaving an environment like that causes problems.

"There has to be a health program with the city of Philadelphia for the people. And systematically, for the whole area, to see what kinds of problems there are. We need information on a concrete level. They will have to do a complete clean-up and a study and evaluation made and tell people that it's safe to come back to their sea activities. Of course, there is some activities that could be worked out to create compensation for the people in the area.

"We want to have a meeting with the mayor of the city of Philadelphia."

The workers stand and, after expressing their hope to meet again in Philadelphia in February, begin their difficult journey back to Gonaïves.

Conclusion

"This is the most heart-wrenching campaign in my 13 years of doing this type of work," says Ann Leonard, who still believes it is Philadelphia's responsibility to resolve the problems the Haitians suffer as a result of the ash.

Councilman David Cohen agrees and takes the issue even further. "The $50,000 seems to be not enough. I think Philadelphia has a continuing responsibility ... It is irresponsible to send [trash] out without knowing where it was going. Philadelphia ought to be part of this agreement.

Philadelphia would have some sort of financial responsibility. Philadelphia clearly has a responsibility, although it's not clear what the limits on that responsibility would be."

Even if Philadelphia could not be held responsible in a court of law?

"I would agree with that."

Though Dr. Franz Latour has nothing but praise for Cohen--"he was the only one who was outspoken on behalf of the Haitian people"--he remains skeptical that anything will be done. "I doubt this will lead anywhere because even when Street was president of City Council, he was one of the persons who was adamant not to do anything. He consistently backed up Mayor Rendell all the time ... Some apologies should be given to the Haitian people and whatever compensation necessary to the nearby population which has been exposed to the trash. ... There has been damage. I am sure of that."

Tropical Salt Corporation (TSC) is representative of that damage. Owned by four people, two of whom are Haitian-American brothers who now reside in New Jersey, TSC lined up investors to start a salt production and distribution facility in Gonaïves. Their intent was to employ 1,500 Haitians as well as start programs such as road development and public waste management.

They were doing this, one of the Armand brothers said, "because we wanted to bring something back to our birthplace." When a story about the ash appeared in the Village Voice in January

1998, all of TSC's investors backed out. Ed Armand says now, "If it weren't for that waste in Gonaïves, we would be in business today."

While it has been shown almost conclusively that the region has suffered loss of industry and income, and has been plagued with health problems related to Philadelphia's toxic ash, there continues to be a lack of action on the subject.

Greenpeace's Kenny Bruno says, "If, for some reason, incinerator ash had been dumped on a beach in France or Britain, Philadelphia would have found a way to get rid of it within a few hours. But because it was in Haiti, it sat there for 12 years."

But Kenny Bruno, as well as Ann Leonard, Robin Hoy, Franz Latour and other activists, is no longer pursuing the issue. They've moved on to more promising battles. Leonard's last letter to Mayor John Street was dated June 2000. When, once again, she failed to receive an answer, she stopped trying.

Aldrin Calixte, though, continues to work toward bringing a delegation here to meet with Mayor Street.

The town of Seguin is Haiti's largest watershed. Here, a Lebanese emigre named Winnie houses many species of birds that can only be found in Haiti. Due to his efforts, the area is now environmentally protected, which puts him at the forefront of a very different kind of environmental movement in Haiti.

After living in Haiti for 20 years, he knows the story of the ash well. He is open and friendly, but has harsh words about what has happened in Gonaïves "America cannot be the leader of the world--claim it, boast about it--and let things like that happen. It's not moral; it's immoral. That's what I say about it. They know exactly how to ... take care of this waste ... But why just go and dump it to the poor guy's backyard? Because it is a poor guy's backyard and he cannot do anything about it. How many Haitians will die because of that?

"This regime found the problem and is trying to deal with it. They at least succeeded in getting it out of the country. But now what? Is Haiti another planet? People should come and visit this planet. How about some real changes?" *

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Basel Action Network is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a `fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond `fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

|