Shipload of Trouble

The Blue Lady case is a litmus test of the Indian government's stand on hazardous wastes.

by Lyla Bavadam (in Mumbai), Frontline (India)

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

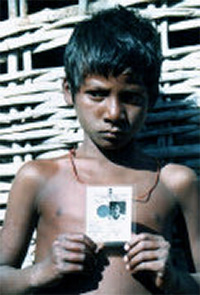

Dinabandhu with the electoral photo identity card of his father, Surendra Sethi, who died in

Alang following an illness. A 2006 picture. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

A decommissioned ship being dismantled at Alang. Local people say that the work at Alang has

contaminated air, water and soil.

©Amit Dave/Reuters |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Nov. 03-16, 2007 –

Controversy is not new to Blue Lady. The 76,049-tonne luxury liner, formerly known as SS Norway and before that SS France, was once the largest passenger ship in the world and has a colourful history.

The ship’s first encounter with controversy was in 1974 when trade unionists commandeered it in an attempt to prevent its sale and also to secure wage increases for the crew. The bid failed and the ship was sold. The following years saw more controversies as the ship aged and its owners thought of ways to make it more profitable.

In 2003, a boiler explosion on the now renamed SS Norway killed seven of its crew and injured 17 in the port of Miami. That was the final straw. The ship was withdrawn and towed first to Germany and then to an anchorage off Port Klang in Malaysia. This was the beginning of the controversy that continues to dog the ship even as it lies beached at Alang in Gujarat.

When a ship leaves a port of origin it is mandatory for the master to present the onward plan. The plan given by SS Norway was that it was being taken to Malaysia to be made into a floating hotel. This, Gopal Krishna of the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Ban Asbestos Network of India (BANI) says, was “clearly fraudulent [considering the severity of the boiler explosion on the 44-year-old vessel]”. But the German port authorities did not challenge it. By now, the ship had changed ownership from Norwegian Cruise Lines to Haryana Ship Demolition Pvt. Ltd. This in itself is an indication that the floating hotel plan was merely a charade. But this was probably not known at the time since it was a proxy buyer who bought the ship.

The ship left German waters in May 2005 and docked in Malaysia. Then it left for Dubai, citing a need for repairs, but actually moved towards Bangladesh where it was refused entry. It was then steered towards India in May 2006, but a timely application in the Supreme Court by Gopal Krishna prevented it from entering Indian waters. With the impending monsoon, the ship’s owners (Haryana Ship Demolition Pvt. Ltd.) pleaded humanitarian grounds and the Court permitted anchorage at Pipavav port near Alang. After getting this permission, the ship sailed to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and returned after 25 days. What it did in that period remains a mystery. On its return it was beached at Alang.

The Supreme Court had given it permission only to anchor off Pipavav for the monsoon and not for beaching. The contention that a beached ship cannot be refloated has been contested in a letter sent by the U.S.-based Crowley Maritime Corporation to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, offering to refloat the vessel.

The master of Blue Lady had given a false declaration saying that there were no hazardous materials when there were 1,100 locations on the ship that held radioactive matter. Blue Lady had close to 1,700 tonnes of hazardous material – two and a half times more than that in the aircraft carrier Clemenceau, which France recalled in February 2006 from Alang, says Gopal Krishna. Besides, the ship did not carry papers saying it had been decontaminated. This should have sufficed to send the ship back since India is a signatory to the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal.

Proxy buying is a common business in shipping. It is a convenient loophole that permits both seller and buyer to evade laws that would result in huge expenses. In the case of Blue Lady, were it to be dismantled, the owners would have had to decontaminate the ship in Germany itself under the Basel Convention. However, decontamination in Europe of a ship the size of Blue Lady would have cost nearly 30 million euros, according to reliable estimates.

In August 2006, Norwegian Cruise Lines sold the ship to Bridgend Shipping of Monrovia for scrapping. The ship was renamed Blue Lady. The bill of sale says the vessel was sold for $10! The ship was to go to Bangladesh for scrapping but the government in Dhaka refused entry because of the vast amount of asbestos on board. It was then sold to Haryana Ship Demolition Pvt. Ltd., which claimed to be the bona fide owner but could not show documents of proof. In July 2006, the ship was sold to its current owner, Priya Blue Industries Pvt. Ltd. in Alang, which, too, has been unable to produce the papers of ownership.

Clemenceau’s sale was also supposed to have been via the proxy buyer system but in this case it failed. A particular clause in the proxy system says that ownership will be transferred after dismantling. The benefit of this clause extends to both the buyer and the seller. If the buyer manages to break the ship, well and good; if he does not, then it returns to the port of origin. The basic idea is to avoid the heavy cost of decontaminating a ship in a Western port of origin. An owner who has to do this attaches the cost he has borne to the sale price when he sells a ship to a ship-breaker. Thus it is suitable to both the seller and the buyer to try and evade decontamination in Western countries.

The proxy buyer comes in at this point. Simply put, the proxy buyer permits a shipowner to dump a vessel without the onus of decontamination costs. This is how it worked for Blue Lady. Norwegian Cruise Lines sold SS Norway to Bridgend for a ridiculous amount, but there is no way to find fault with Norwegian Cruise Lines since it can sell its ship for whatever price it chooses. Of course, it does not take much imagination to figure out that the real price is paid off the record, which explains why proxy buyers are also known as cash buyers.

Once the deal is made, the proxy buyer usually changes the ship’s name so that the original owner can further distance himself from the affair. In this case, SS Norway became Blue Lady. The next step towards dismantling was easier – Bridgend sold the ship to Haryana Ship Demolition, which in turn sold it to Priya Blue. Thus, the role of the proxy buyer is primarily to enable shipowners to keep their reputation and also avoid the cost of decontamination.

Now that Blue Lady is beached and the Supreme Court has permitted its dismantling, a 12-point guideline for worker safety has to be adhered to. This includes procedures for decontamination and correct disposal of toxic waste. Dismantling has not yet started because the ship-breaker has not been able to comply with all the requirements.

It is estimated that Blue Lady has close to 1,700 tonnes of waste such as asbestos, asbestos containing material (ACM) and radioactive material, namely Americium-241. Even its owner Priya Blue confirms this. According to the United States Environment Protection Agency, Americium-241 can stay in the human body for decades if ingested or inhaled or if there is direct external exposure to its alpha particles and gamma rays. Exposure to Americium-241 poses a cancer risk.

It is now acknowledged that dismantling of ships has effects that go far beyond causing harm to those who are in immediate contact with the materials. Air, surface water, groundwater and soil have been contaminated over the decades. Local villagers have decided that enough is enough. Bhagvatsinh Haluba Gohil, sarpanch of Sosiya village in Bhavnagar district, and the sarpanches of 12 other villages, have filed an application in the Supreme Court to halt the dismantling of Blue Lady, on behalf of 30,000 villagers who live within 25 km of Alang.

They argue that “the dismantling of the ship would have hazardous effect on the residents of the villages near the Alang ship-breaking yard as the ship contains large amounts of asbestos”. They have submitted that Rule 12 (i) of the Hazardous Wastes (Management and Handling) Rules under the Environment Protection Act, 1986, bans the import of asbestos. The court is yet to deal with the application.

“We don’t want to stop ship-breaking because that would mean loss of jobs for hundreds of people. All we are asking is that it be done in a responsible manner and our lives and earnings are not affected,” says Gohil.

He adds that the open dumping of waste into the sea has affected the fishing community too. “Fishermen are forced to go out into the sea beyond five or six kilometres because of the waste oil that spreads over the water and ruins their fishing,” Gohil says.

Speaking to Frontline, Gohil explained what prompted the villagers to take the legal step. “For the past 15 to 20 years we have been noticing a diminishing of our crop. It has not been easy to pinpoint this but we have now come to the conclusion that it is related to air, water and soil contamination brought on by the work at Alang.”

The livelihood of the villages comes primarily from horticulture, and Gohil says that the trees are now far more susceptible to insect attacks than before. He says farmers’ expenses in the purchase of pesticides have gone up considerably.

Years of ship-breaking in Alang has meant that the toxic materials have slowly leached into the ground. Gopal Krishna says the report of the Technical Experts Committee on Hazardous Wastes relating to Ship-breaking confirm that the groundwater in Alang is heavily polluted. This admission by an official report is part of the irony of the fight against hazardous waste. On the one hand the government accepts that material like asbestos are hazardous to health and the environment but, on the other hand, the policies of the government do not reflect this concern.

Vidyut Joshi, the former Vice-Chancellor of Bhavnagar University, has made a study of ship-breaking in Alang. His conclusion is that it should not be the business of the Gujarat Maritime Board to supervise industry operations at Alang. This should be given to the Industries Department, which is better equipped in terms of skills to handle labour issues, detection of hazardous materials, and so on. The present system has the Maritime Board subcontracting everything to consultants.

The Blue Lady case will be a sort of litmus test not only for the Indian government’s stand on hazardous waste but also for Europe. At present the position of both is suspect.

Earlier, Clemenceau was allowed into Indian waters though it had flouted Indian laws. France recalled the ship only because of intense public and legal pressures in that country. Last year, the Riky, another asbestos-laden vessel, left Danish waters under misrepresentation and was dismantled in Alang. The Danish government is pursuing the matter and has initiated criminal proceedings against its owner.

This is in direct contrast to the reaction of the German government, which has refused to take any responsibility for Blue Lady. The ship left German waters under conditions that could have been (but were not) challenged by the German government, and now Germany is refusing to accept any responsibility for the ship, saying it is not a state-owned vessel as Clemenceau was. This is irrelevant since the Basel Convention dictates terms on the basis of the hazardous nature of the waste and not on the basis of ownership.

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Basel Action Network is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

More News

|