|

By Jeff Johnson, Chemical and Engineering News, Volume 79, Number 6 5 February 2001 -- Critics warn that U.S. mercury policy is helping fuel use in the developing world Last September, Holtrachem Manufacturing Co. shuttered its mercury cell chlor-alkali plant in Orrington, Maine, and joined a growing list of U.S. companies that have ended their use of mercury-based technologies. In HoltraChem's case, the troubled company just wanted out of the chlorine and sodium hydroxide business, the plant manager says. And, like all prudent executives, HoltraChem's managers began to sell off the company's equipment and raw materials, including 130 tons of mercury.

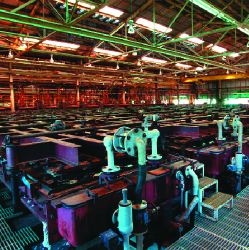

It sold the stockpile to D.F. Goldsmith Chemical & Metal Corp. of Evanston, Ill., one of a handful of U.S. metals brokers that trade mercury. Goldsmith resold it to buyers in India for use there, company President Donald F. Goldsmith says. All of this is perfectly legal and is nothing out of the ordinary, Goldsmith stresses. "It is a fairly common occurrence as many chlorine-caustic operations have either closed in the U.S. or switched to membrane-type technology systems that don't employ mercury. In either case, they want to get the mercury out of there," he says. But this trade was different. A combination of U.S. and Indian activists have raised Cain over the deal. They question the logic of U.S. government policies to keep mercury out of its environment at high costs to U.S. industries and then allow unfettered shipments of the neurotoxin to the rest of the world. Madhumita Dutta calls it "toxic trade." Dutta is coordinator of Toxics Link, an Indian toxics information clearinghouse. "It's toxic trade when a country like the U.S. that knows the dangers of mercury and is taking action to get out of the mercury trap has no qualms about exporting the problem to India, a country where regulations are even less capable of dealing with the poison," he says. Dutta and other Indian organizers have joined Greenpeace and a broad range of U.S. groups, mostly in New England, that want surplus mercury pulled from the world marketplace and consequently have focused on this shipment. They have managed to get the issue onto the pages of the Indian press. At this time, it is unclear exactly where the first installment of HoltraChem's mercury is, Goldsmith says. Officials with the Environmental Protection Agency and State Department said the shipping company had held the 18 tons of mercury up at Port Said, Egypt, at the mouth of the Suez Canal. Rumors had circulated that Indian dock workers would not unload the mercury and environmental activists would protest its arrival in the Mumbai area. Goldsmith says it is not clear where the shipment will eventually be unloaded. "We have customers around the world that would be very happy to have this mercury," he adds. INDIA IS ONE of the top destinations for U.S. surplus mercury, according to figures tabulated by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The most recent USGS figures show that in 1999 Indian buyers imported 85 tons of mercury from the U.S. This one sale will exceed the 1999 total, however, and the surplus mercury from the U.S. and most of the developed world is going to grow in the future, according to Robert G. Reese Jr., a USGS analyst. He points out that there will be less mining for virgin mercury in the world and more reliance on recycled mercury. Reese emphasizes that accurate data are hard to come by in international metal trades but says about 1,800 tons of mercury was mined in 1999, only about half the amount of five years earlier. The U.S. is among a dozen countries with mercury resources, but it has not mined mercury for a decade. Instead, because of concerns over mercury contamination and EPA regulatory pressure, the U.S. has cut back on mercury in products to the point that it has become a net mercury exporter. USGS ESTIMATES that in 1999 U.S. companies imported 62 tons of mercury and exported 181 tons, all recycled from mercury sources. Mercury use in the U.S. has plummeted from more than 2,000 tons in the early 1980s to less than 500 tons today, according to USGS. A similar drop is true for price. Over the same period, mercury fell from around $600 for a 76-lb flask to around $150 today in 1992 dollars. In the mid-1960s, a flask of mercury was worth more than $2,000 in 1992 dollars. Critics charge that a slowly building wave of recycled mercury and bargain prices on the international market may actually encourage mercury's use by companies and individuals that only a few years ago would have been turned away by the higher price. Frank R. Anscombe, an EPA mercury specialist, says there are well-documented reports that mercury is used in developing countries for gold prospecting, skin-bleaching cosmetics, dubious "snake-oil" medicines, batteries, and as pesticides--all uses that are not allowed in the U.S. The impact of mercury emissions not only can be felt by local people and their environment, but can also adversely increase the global atmospheric mercury burden. For instance, back-country, low-tech gold mining is notorious for its mercury air emissions, he says, and is one of the leading sources of mercury emissions on a global scale. But Bruce Lawrence, president of Bethlehem Apparatus Co., Hellertown, Pa., a mercury recycler, disagrees. He counters that it will be used in these countries just like it is used in the U.S.--in chlor-alkali plants, thermometers, fluorescent lights, dental fillings, and electrical switches. "In the developing world, as countries become more industrialized, they will use more mercury," he says. "They need it for better dental hygiene, lighting, and electrical equipment." However, little is known about how mercury is used in the developing world, say Reese and others who track mercury. Goldsmith says he sells mercury to a broker in another country who resells it to others. He says he has no idea where it winds up. Reese notes that mercury is a freely traded commodity, despite its toxicity. He adds that only a few years ago Hong Kong was the largest buyer of U.S. mercury and was trading it to China and around the world. But like an elephant, the big mercury inventories are hard to hide, and that comes right back to the chemical industry. The largest single mercury inventory is held in the world's chlor-alkali plants, more than 86% of which are outside the U.S., according to USGS. Looking just at the U.S., USGS figures that as of 1996 slightly more than 3,000 tons of mercury was held in inventories at mercury-cell U.S. chlor-alkali plants, the only one of three technologies to produce chlorine and caustic soda or sodium hydroxide that uses mercury. That total tonnage is probably already smaller as a result of the shrinking number of plants and a new effort by the industry to cut mercury use. But maybe not, because figures in the world of mercury are notoriously inaccurate. Still, the U.S. numbers are huge, and worldwide inventories for these plants could be truly monumental. A rough calculation applying USGS figures to the world would put the international inventory at more than 20,000 tons of mercury held in chlor-alkali plants. The largest single stockpile in the U.S., however, is under the control of the Defense Department. It amounts to some 4,381 tons of mercury, left over from a time when mercury was used in the production of enriched uranium for nuclear weapons. DOD had been selling off the reserve until 1994, when concern was raised over the impact on uncontrolled mercury use in the rest of the world. Now, environmental activists would like to use that same concern to halt the export of chemical industry inventories. "Recovered mercury should be considered a liability and set aside as a dangerous waste," says Michael T. Bender, executive director of the Mercury Policy Project, a New England-based group that advocates phaseout of mercury. Bender says mercury has become an economic issue as much as an environmental one.

"With so many businesses, municipalities, states, and even the federal government spending millions of dollars to keep mercury out of the environment," Bender contends, "does it make any sense to allow mercury to be sold for a few dollars a pound and then tossed back into the environment The government is asleep at the wheel." Over the past few years, EPA has required or proposed that mercury emitters--garbage and medical waste incinerators that burn mercury-tainted wastes and coal-fired power plants--install controls to cut emissions. The most recent regulation proposed for coal-fired power plants is estimated by EPA to cost $15,000 to $50,000 per lb of mercury captured from stack gases (C&EN, Jan. 1, page 18). But mercury costs only about $2 per lb for use in manufacturing or new products. And without tight controls, these uses can lead to more mercury emissions and a higher global budget. Bender urges that recycled mercury be joined and stored with defense stockpiles while a national strategy for retiring mercury is developed. In the case of the HoltraChem shutdown, the governor of Maine and other New England officials made the same request to DOD last year. They were turned down. "By selling its mercury, HoltraChem was following existing EPA regulations," EPA's Anscombe says. "With the great ebbing of U.S. demand, there is no current regulation for returning mercury to the earth, from where it was originally mined. Another issue is who would pay for retiring mercury HoltraChem is responsible to its shareholders to sell its assets. An innovative approach respectful of the property rights of mercury holders would be for the federal government to purchase surplus mercury." EPA HEADQUARTERS staff says mercury is a commodity, and as such the government is reluctant to buy it to take it off the market. The agency, according to the staff, would look to Congress to enact legislation giving EPA specific authority to buy the mercury. The agency has a small research effort under way to identify ways to sequester mercury.

Bender and others note a history of government entry into the marketplace to purchase agricultural commodities as well as buying up excess enriched uranium and plutonium from Russian nuclear weapons to keep the metals out of commerce. Mercury traders and chemical industry representatives are skeptical of such a plan. "How do you retire an element" Goldsmith asks. He worries that retiring surplus mercury will increase mining, effectively bringing more mercury into the environment. In the short term, Bender says Goldsmith might be right, but Bender believes that in the long term there is "plenty of mercury out there already to handle most needs of developing nations." Meanwhile, he says, the government should move quickly to find a safe, long-term sequestration technology. He adds that traders like Goldsmith and Lawrence are the only ones who actually understand the mercury market, and consequently the government should look to them to determine how to retire some of the U.S. mercury supply when it far exceeds national need. The Chlorine Institute, a trade association of the chlorine industry, has not taken a position on retirement of mercury, says Arthur E. Dungan, the institute's vice president for safety, health, and the environment. He agrees that mercury use is falling fast, noting that the number of U.S. mercury-cell plants has shrunk from around 35 decades ago to 10 by the end of this year. At one time, about 35% of U.S. chlorine came from the technology versus about 10% today. THE INDUSTRY has also embarked on a program to cut use by 50% and in the first three years has reduced mercury use from 160 tons per year to 88 tons. Dungan also notes that EPA regulations make it impossible to site a new plant, and eventually the technology will be phased out in the U.S. "Eventually, however," he says, "is a long time." The plants have a life of at least 60 years, and U.S. factories have a lot of time left. "But if not now, at some point there will be a mercury surplus," he says, "and there is a need to develop a strategy and options to address this issue." Activists like Bender plan to up pressure on the new Administration to retire mercury from use. He and others made the same request to former EPA administrator Carol M. Browner and the Clinton Administration with no luck. But because of the makeup of the Bush Cabinet, Bender thinks this time may be different. In the mid-1990s, DOD considered selling some of its mercury stockpile, but the governors of several states strongly objected to the Clinton plan. Now two of the leaders of the states' effort--former Wisconsin governor Tommy G. Thompson and former New Jersey governor Christine Todd Whitman--are in key positions in the Bush Administration as, respectively, secretary of Health & Human Services and administrator of the EPA. In letters to the Clinton Administration at that time, Thompson and Whitman noted the efforts that states had made in cutting mercury's use in products and in limiting emissions. They called the DOD sell-off of mercury a subsidy to encourage use and urged the federal government to withhold defense surpluses from the marketplace. How they feel today might shape the mercury debate.

MYSTERY Buried in a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) mercury report is a reference to "101 tons of missing mercury," turned up by a mass balance examination of mercury use by the chlor-alkali industry. The report is the most recent USGS mercury study but relies on data from 1996. It notes that industry self-reported data for that year show some 35 tons of mercury annually exits U.S. chlor-alkali plants in the form of environmental air emissions (8 tons), in product (1 ton), and in waste going to landfills or off-site recyclers (26 tons). However, the report says that in that same year industry purchased 136 tons of mercury. So where is the unaccounted mercury The report adds that the missing mercury has been the subject of intense scrutiny by industry and the Environmental Protection Agency. EPA is well aware of the question, it appears. In an internal document, from a few years ago, EPA staff warned that if the figure is correct, the world's 250-plus mercury cell factories are the largest source of international mercury pollution. Industry sources argue the issue is largely moot today. Led by the Chlorine Institute, over the past five years U.S. factories have reduced mercury consumption by 42%, and further reductions are forecast. Also in 1999, Olin Corp. invited EPA scientists and others to study a plant over a 10-day period to develop better data on nonstack air emissions (C&EN, April 26, 1999, page 8). EPA sources applaud the progress and attribute it to investments and operational changes, noting that the U.S. industry is responsibly going well beyond planned regulatory requirements. While encouraged by emissions measured during the Olin study, which came close to lower estimates, EPA staff still worry that a study of such short duration may miss important operating events and believe an additional study is needed to account for mercury consumed by factories. Chlorine Institute officials stand behind their numbers and say any missing mercury might be contained within piping or other places on-site. But company executives in other industries that have faced costly mercury emissions reductions are not so forgiving. They have noted that EPA bases its regulatory decision on the worst polluters. And if the 101 ton figure is accurate, it would dwarf the mercury emissions of medical and solid-waste incinerators (around 50 tons each per year) as well as coal-fired power plants (around 45 tons per year) which are making costly improvements. These point sources are much easier to measure and monitor than fugitive emissions from an open building that holds highly volatile mercury in cells, heated to several hundred degrees Fahrenheit. An engineer not associated with EPA or the chemical industry called the missing tons "the problem no one wants to talk about because everyone is afraid what the answer might turn out to be."

HEALTH RISK Ironically, because of the nature of mercury, the U.S. may get back some of what it has exported in the not-too-distant future. Mercury is a uniquely insidious substance because of its mobility within the biosphere. The only metal that is a liquid at room temperature, mercury has a high vapor pressure and can be transported long distances via the atmosphere before being deposited back to Earth, making it truly an international pollutant. Simple bacteria can naturally convert elemental mercury into a methylated form that was proven at Minamata, Japan, in the 1950s to be lethal or maiming to humans when consumed in high doses by eating contaminated seafood. In lower doses, mercury has been shown to be a neurotoxin that bioaccumulates in animals and humans, with greatest impact on the developing fetus. It is the cause of the greatest number of fish consumption advisories in U.S. waters. A report by the National Research Council estimates that 60,000 U.S. children may be born annually with neurological deficits due to mercury exposure in the womb (C&EN, July 17, 2000, page 12). FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Basel Action Network is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a `fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond `fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. More News |

|

|